7-8-9 October 2016

This event is not open to the public.

The Easter 1916 Rising was a short-lived and unsuccessful rebellion that sowed the seeds that would lead to the Irish War of Independence, the eventual establishment of the Irish Republic and, indirectly, to the disintegration of the British Empire.

Historian Charles Townshend notes in his book “Easter 1916: The Irish Rebellion” (2006) on the subject that “Ireland’s Easter Rising is one of the handful of modern historical events that instantly created its own mythology and changed millions of lives forever.” In her more recent cultural history, Dublin 1916: The Siege of the GPO (2009), Professor Clair Wills calls the 1916 Rising “[t]he defining act of rebellion against British rule and the most significant single event in modern Irish history.” “The Easter 1916 Rising,” says Professor Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh, “is one of the pivotal events in the history of twentieth-century Ireland” and one that had “global significance” for the history of “national liberation movements of the twentieth century.”

With the Centenary of the Easter Rising in 2016, it is time to take a fresh look at both the events associated with the Rising and their significance in world history. This conference aims to consider the dramatic events of 1916 and to set them in a broad and balanced perspective. A key theme of the symposium will be: Where does the historian place the Easter Rebellion in its European and global contexts as anti-colonialism found its voice in the wake of the First World War? Other themes are related to Ireland in 1916 as a place of intense flowering of intellectual and artistic activity—particularly in Dublin, the second city of the Empire; feminism and citizenship; the role of America in the Rising; the politics of commemoration; and the legacy of 1916 today.

In 1916, Europe was in the midst of the greatest and most violent conflagration the world had ever seen. The First World War ushered in a century of momentous change. As millions died on the Western Front, empires were crumbling. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was no more. The Ottoman hegemony had dissolved. Russian imperial sway yielded to a violent revolution and civil war. For all that, hopes rose that in the wake of the traumatic war, the desire for “self-determination” in the far-flung colonies of European colonial powers might come to fruition.

As the Great War ravaged Flanders and killed thousands of combatants on both sides, many Irishmen served under the British flag, playing their part as they saw fit in what was promoted as the war to save small nations. The British Army included thousands of Irishmen with nationalist leanings who favored Home Rule for Ireland along with thousands of Irishmen who opposed Home Rule and who swore a covenant to keep their nation in the Union of Great Britain and Ireland established in 1800. Both Irish nationalists and Irish Unionists (as they were called) believed that their valiant participation in the British Forces would favor their cause at home.

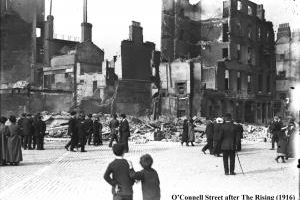

At the same time, in Ireland, a much smaller body of men and women took up arms against that same British Empire to claim Irish independence. On Easter Monday 1916, this group, led by poets and idealists, took over a number of key buildings in Dublin to proclaim the establishment of an Irish Republic. While their actions took the British authorities completely by surprise, within a few days their rebellion had been summarily suppressed, the center of Dublin lay in ruins, and the leaders of the insurrection were court-martialed and sentenced to death. However, the force with which the rebellion was suppressed was a significant factor in turning public opinion from an initial hostility to the insurgents and their actions to a growing sympathy to their cause. On the one hand, it swayed the majority of nationalist-minded Irish (mostly Catholic) from their loyalty to Home Rule and the Irish Parliamentary Party into support for the emerging force of the separatist party Sinn Fein. On the other hand, for those who strongly supported maintaining the union with Britain—the Unionist population (mostly Protestant) in Ireland—the Rising confirmed their worst fears regarding nationalist treachery.

The crucial role of the United States and of Irish America in the Easter Rising has been frequently overlooked; but in fact, the United States is central to the story. Five of the seven signatories to the Proclamation of an Irish Republic had spent periods of time in the United States—and that was to prove significant in the development of their thinking and actions. One of the few leaders not executed and the future president of Ireland, Eamon de Valera, was born in New York City in 1882. The centrality of America to the Rising, and the interest of Americans in how the rebellion unfolded, is demonstrated by the fact that stories relating to the events in Dublin occupied front-page columns of The New York Times for 14 consecutive days.

The 1916 Rising is the point of no return in Irish history. For Home-Ruler and Unionist alike, nothing emerges as anticipated. In its aftermath, John Redmond, the Irish Nationalist champion of Home Rule, dies with his vision of Home Rule vanished forever; and Edward Carson, the Dublin-born hero of the Unionist cause, is granted what he had always resisted in the name of the Union: Home Rule (for Northern Ireland.)

Even before the Great War, the early 20th century was marked by an intense flowering of intellectual and artistic ability in Dublin, the second city of the Empire. In the Irish Literary Revival, all the major literary figures rubbed shoulders with the lawyers, educators, and political activists of the time. Union leaders, suffragettes, poets, polemicists, propagandists, and journalists moved in the same circles as James Joyce, W.B. Yeats, J.M. Synge and, subsequently, Seán O’Casey. Thus, there are overall humanities themes to be teased out of the historical significance of the Easter Rising, the rise of anti-colonialism and the end of the British Empire, the internationalization of Irish politics, and the Global War and its impact.

The Irish Rising had reverberations around the world. In its aftermath, anti-colonial movements in places like India and Egypt looked to Ireland for lessons learned. Lenin observed of it: “A blow delivered against [the] British . . . in Ireland is of a hundred times greater political significance than a blow of equal weight in Asia or Africa. It is the misfortune of the Irish that they rose prematurely, before the European revolt of the proletariat had had time to mature.”

Thus, what might be portrayed as a relatively minor event—an armed insurrection in a small country on the fringe of Europe that was defeated within a week and that was not even countrywide but confined to a small, if central, part of Dublin—in fact attracted worldwide attention and achieved global significance.

Professor Christopher Fox & Professor Bríona Nic Dhiarmada

Symposium Co-Directors